If I hadn't loathed the man so completely, I would have discovered the true nature of Ashley before he had done so much damage. I console myself that even a specialist in occult psychology can be forgiven for not recognizing a seemingly mythological figure walking - or should I say stalking? - the ivied and ivoried, halls of academe. My university is not Lovecraft's Miskatonic, but a more mundane institution. Call it Joshua, for the Joshua trees which stand outside.

Our department, Psychology, is of moderate size, having fifteen men and five women. I am the senior woman, condemned to a life as an associate professor by my occult specialty (peripheral they call it) and my race - I am black - as well as my sex. I need not belabor the politics. Friends call me X.C. My full name is Dr. Xanadu Christabel Isom which has undoubtedly served to strengthen my character. I've often found it ironic that in her devotion to Coleridge, my mother named me after a fantastic kingdom produced in a drug dream and a woman threatened by what amounted to a vampire.

Of course, only three other people are aware that I am responsible for freeing Joshua U. from the curse of Ashley, or even that he was the curse.

At thirty-nine, Ashley was ten years younger than I. His six feet five inches made him the tallest of the non-basketball faculty. Shoulder length curly, gray-brown hair and short pointed beard framed a demonic face, giving him the appearance of an evil parody of Christ. While he was not fat, he appeared soft and unmuscled in a most unsavory way. He alternated between ruddiness and an unhealthy pallor, which we told ourselves and each other was the result of booze or drugs. Some days he seemed much larger than others, glowing with vitality and health, on others he seemed smaller, malevolent and predatory. I hate to use the word predatory as I am a great fan of such magnificent predators as the wolf, perhaps vulturine would be more appropriate.

Other than his size and the piercing quality of his eyes, his greatest weapon was his voice which increased in volume with his size. He spoke in a thick southern accent which became increasingly exaggerated as time went on. I found this terribly distressing as I thought that I had left the good old boys behind with my accent, when I fled to the west. The south had risen again in more ways than one.

In our infrequent department meetings, Ashley drained the life out of all who opposed him. He seemed almost to glow and his skin to plump out as his opponents shriveled. As time went on, even his supporters desiccated before my eyes. "Meglomania," whispered people in the halls, and some of us even made jokes that he was an energy vampire feeding on the essences of his enemies and, perhaps, his friends.

What first seemed an epidemic of anorexia began to sweep through a number the younger members of the faculty. I joked that I would be delighted to come down with a mild case, about twenty-five pounds worth. It soon ceased to be a joke. The victims were afflicted with severe lassitude and anemia that could not be wholly controlled by blood transfusions. They began to die.

Members of the Infectious Disease Task Force from Atlanta were dispatched to Las Vegas while every attempt was made to keep the nature of the disease secret.

Word leaked out from family and friends of the afflicted that they shared a bizarre dream in which they were swimming upstream in a viscous fluid their arms becoming freezing cold. Researchers looked desperately for a cause. Theories that the disease was either a form of AIDS or leukemia circulated and were soon disproved as the doctors faced a blank wall. Researchers became increasingly reluctant to further weaken the patients by continually withdrawing blood for analysis and coming up blank.

The common denominators of the victims were that they were all young and attractive, whether male or female, and were members of the Phoenix faculty, either full time or part time. All were untenured, a bizarre twist. I thought of the Chairman of the German Department who had once remarked, "I only harass the untenured faculty, never the tenured."

There was no common denominator in terms of department, building in which they worked, sexual partnership, or race or religion. Many were not even acquainted. They shopped at different grocery stores and frequented different restaurants. Some drank from the campus water supply and ate at the student union, others did not. Some were married and some were not. Those who were married or involved in relationships did not communicate the disease to their partners. Even the victims' library usage was analyzed.

Strangely, the disease did not spread to students, another bit of evidence that some sort of intelligent selectivity was being used as far as I was concerned. By the time that twelve young faculty members had died, it became obvious to the public as well as the faculty community that something was terribly wrong.

What made me suspect a cause that lay outside of traditional science was that all of the victims, both male and female, were young and attractive, non-tenured and non-student, a degree of selectivity which seemed far too large to be coincidental and which, to me, meant that there was a psycho-sexual basis of some sort. The medical researchers had felt that physical attractiveness was a quality that could not be determined empirically and had dismissed it as coincidence.

Once I had decided that the illnesses were the result of a human agent, it was necessary only to determine the identity of that agent. The tests done by the Atlanta Task Force had ruled out poison, at least poison as any of us knew it. Most of us were getting pretty worn and worried, even those of us who were not in the group considered at risk. We had, by now, all lost people that we cared about or at least liked, and the untimely destruction of so much youth and vitality seemed particularly horrible to those of us who had reached middle age, although we had to admit that we were grateful that we had been spared thus far. About the only person who seemed to be thriving was Ashley, who seemed to take a ghoulish delight in talking about how horrible it was and how incompetent the doctors were and in giving his version of comfort to the families of the victims.

At first people tried to believe that his intentions were good, but it soon became clear to some of us that he had found another way to bully people. That he was a bully no one denied, but most put it down to his redneck origins and tried either to forgive or ignore him.

His specialty was sensory deprivation research, a peculiar interest for one so verbal, vulgar and assertive. That he owned a number of sensory deprivation chambers, lidded bathtub like boxes in which the subject floated in a saline solution, had been a key factor in his hiring. Grants had been drying up, and a new faculty member who came complete with his own lab seemed like a bargain. No one had thought to inquire why he personally owned eight of these boxes, a serious oversight as we were to discover. P. U. was nothing if not cheap.

While everyone in the department agreed that he was power hungry and dangerous, he had somehow managed to get himself elected chairman and proceeded to make life hell for all but a handful of henchmen.

While he had published a few articles early in his career, he hadn't done any real research for several years before arriving at Phoenix. He kept his laboratory locked and refused to allow anyone in except for his sidekick Rhinefeldt, a dismal little man who had been granted tenure out of pity. As Miner said, "I'd never truly known the meaning of word sycophant until I saw Rhinefeldt sliming his way behind Ashley," who did, by the way, spend several hours each day locked in his lab. We assumed from his lack of publication that he was taking drugs or sleeping off his continual boozing.

A good wind had blown my way with the arrival of the Atlanta team. During the investigation, I had rediscovered in Leroy, the forensic pathologist, a friend who had been entering Howard University as I was graduating. It was hard to see the scrawny kid that I had known in the huggable, chocolate walrus that he had become. I found him comfortable and attractive, and he reciprocated. We took to spending long evenings sitting on the floor at the Fez Moroccan Restaurant where the food was good and we were never hurried.

One night between sips of mint tea, I got up the courage to ask him if there had been any odd puncture marks on the necks of the victims. He laughed, asking if I believed in vampires, and said "No." He had, however, noted strange marks inside the armpits of several of the victims that he had autopsied and we made jokes about a vampire with an armpit fetish and dropped the subject.

A couple of days later, Ashley called me into the office on some pretext or other, but mainly to harass me. As I was deciding how much I was going to put up with, I suddenly registered the office decor. There were several pictures of handsome women, all with their arms in the air, all displaying vistas of arm pits. It was a reality shift. Suddenly I knew that it had to be Ashley. I was so stunned that I muttered an apology for whatever it was that I hadn't done and almost stumbled out of the office.

I didn't need this. Life is hard enough for a parapsychologist, without stumbling on a vampire in the l980s. The whole thing was impossible.

I reviewed my vampire lore and tried to fit Ashley in. He wouldn't go. As far as I knew, he reflected in mirrors just like anybody else, he adored garlic, and didn't seem to have any problems with basic Christian symbols, as could be seen by his attendance at church services for many of the victims. The only way that I could make him fit at all was to make a quantum leap and assume that he was a psychic mutation of some sort, perhaps left over from the battlefields of the Civil War. The psychics in the twenties had maintained that nature of death on the battlefield in World War I had left many vampires without rest.

If he was, then the marks on the armpits could well have been made by him, perhaps as a kind of sexual perversion. Leroy had said that the armpit was a good a source for blood as the neck. Maybe with today's new sexuality the only way he could get kicks was to do something kinky. I giggled at the idea that if he wasn't careful the aluminum in the deodorant would give him Alzheimer's and we'd have a forgetful vampire running around.

I still had to deal with coffins and native soil and the fact that he was around for all but the few hours that he locked himself in his lab each day. It didn't take too long to see the isolation chambers as twentieth century high tech coffins.

My problem now was to get a look inside one of the coffins, I caught myself, isolation chambers without Ashley discovering me and without making a total fool of myself.

I was in my office worrying about this when Nancy, my favorite custodian, came along, pushing her trash can cart and stopping as usual to chat. We are both from Virginia which gave us a bond of some sort, and we often talk about conditions at Phoenix which don't seem much better for the janitorial staff than for the faculty.

She shared my loathing for Ashley. "He treats me like I am deaf, dumb and blind." I took a chance and asked her if she could get me a key to his lab.

"I never do anything they can see, or say anything in front of any of them. Just make sure that you keep your eyes open when you come into your office tomorrow." I did, and found the key under the telephone. I slipped it into my purse. The next day was Nevada Day, a holiday in the state, so that I was fairly certain of not being interrupted in my investigation. I had decided not to tell Leroy. Things were too nice on that score for me to risk him thinking me a nut.

There is no doubt that I was worried. I was going to be in a world of hurt if I marched into Ashley's lab and found him sitting there reading a book. I knew that he was trying to set me up and he would probably try to nail me for breaking and entering, and I couldn't very well plead that I was just investigating to see whether or not he was a vampire.

It was 1:00 o'clock before I got up my courage to go in. The lab was divided into two rooms. The one in the front held a desk with a dirty ash tray - he smoked like a fiend - a couple of chairs, a bookcase and a filing cabinet. The room was empty. That meant that he had to be in the back room. That I am a devout coward had never occurred to me before but I realized that I was terrified. What if Rhinefeldt was in there with him?

I chickened out, went home, invited Leroy over for dinner, chicken dinner, and told him what I had been doing. He let me know that he considered me certifiably crazy, but he gave me a walrus hug and agreed to go with me to offer what protection he could if I were caught. Of course, now both of our jobs were on the line.

We were going to wait for Thanksgiving for our caper, but Tollofson's death made it pretty clear that we had better not mess around if we thought there was any chance that we might be correct, so we decided on Sunday.

For the first time Leroy spent the night, but in the morning he was even more nervous than I, and we hadn't been too successful in coming up with a reasonable story if we were caught. Ashley's car was parked in front of Main Hall, but Rhinefeldt's was nowhere in evidence, a good sign. Letting ourselves in, we walked through the outer office and unlocked the inner office, the same key fortunately fitting both locks. The isolation chambers were laid out in a neat row. There was no sign of Ashley.

We opened the nearest chamber. It was empty, as were the next three. We were so edgy that we almost said the hell with it, when Leroy lifted the lid of the fifth. In the bottom was three inches of red Georgia soil.

"Oh my God, Leroy, I'm scared!"

"Me, too," he whispered, as he opened the sixth chamber. There was Ashley, just as in all the stories. His eyes were wide open, bright and glittering, frightening even without their usual hypnotic focus. His lips were pulled back in a rictous beneath the Van Dyke beard, so incongruous with his hippy hair, and the classical teeth were in evidence although not so long and exaggerated as I would have expected. For a horrible moment, I thought that he was going to sit up and say, "HaaH! Y'all."

Leroy shut the lid and pulled me out, remembering to leave everything as we had found it. "Now what the hell do we do?"

"Oh, Miz Scarlett, I ain't had no experience birthin' babies!" I shrilled. When in doubt or scared, I always go for humor.

Leroy looked like he was wanted to hit me.

Our vampire lore was obviously all out of date, and I was pretty sure that a stake through Ashley's heart at the crossroads, even if I could find a crossroads not covered with asphalt would probably have no effect and might well interest the police. I knew someone who could make silver bullets, but wasn't certain that they would work either. We said the hell with it and went to the Fez.

Filled with wine and good food, we finally came up with a plan. We would have the isolation chambers moved out, ostensibly for repairs, and have the one containing Ashley delivered to Leroy's forensic pathology lab. Nancy had thoughtfully brought me some of Ashley's personal memo paper, so we were able to construct the necessary paper work, in case anyone should question the removal, which had to take place during working hours. By now we had added two more persons to our task force, Dirk, a biologist and cabalistic magician that I had consulted during my parapsychological studies, both for his open mind on the subject and for his physical skills which were tremendous, and Steve, a young writer of horror stories who could be counted on to be sympathetic and to keep his mouth shut.

It was a simple enough matter for us to concoct uniforms for them to wear while transporting what we now called the coffins. We decided to move only two of the coffins, the one with Ashley and one of the empty ones.

The removal went off without a hitch and by 2:30 in the afternoon, the four of us were in Leroy's lab, staring into Ashley's face, still without a plan of action. We knew that we had to hurry because he was always roaring around the department late in the afternoon.

Dirk and Steve were of the opinion that the first thing that we should do was to make a magic circle around in his isolation chamber. Leroy and I were ready to listen to anything by this time, and watched quietly while Dirk, with Steve's assistance, drew the circle of protection, alchemy and modern science melding for the moment.

At about that moment Ashley made a sound, and the four of us froze. His eyes blinked, but he didn't seem conscious. Leroy had an inspiration and got his halogen lamp out of next room and rigged it to shine directly on Ashley's face, hoping that the daylight spectrum of light would keep him unconscious. It worked.

I was so tense that I ground my teeth and loosened a filling. With the pain came revelation. In all of the vampire lore that I had studied, with all of the varied ways of getting rid of vampires from stakes through the heart to decapitation, no one had ever thought of the simplest expedient.

"Leroy, I've got it! Pull his teeth or his fangs or whatever they are. We don't even have to kill him! What's a vampire without his fangs?"

Dirk and Steve looked stunned. It was heresy, but not they admitted, a bad idea for a starter.

Leroy wasn't any too happy about messing around in Ashley's mouth, particularly with those eyes staring up, but he got out his pliers. Then he wanted to close the eyes, but we wouldn't let him. "Shit, man. That could wake him up!"

For some demented reason, Twain's story of the dentist Tushmaker, who extracted a man's whole skeleton by pulling a tooth whose roots were wrapped around his right big toe, and sending him home in a pillow case, ran through my mind and I started to giggle. The looks that the three men gave me made at that made Ashley look friendly.

The nastier they looked, the more I giggled. Dirk took a step toward me, "What the fuck's the matter with you?" His Green Beret training had convinced him that I was cracking up. Men have no sense of humor.

"We forgot the pillow case." I was by now doubled over with laughter, but somehow managed to convey that I was all right, and the tension was broken.

I regained control and Dirk went to help Leroy, pulling Ashley's jaw down and peeling back the lips. I picked up a metal bowl to hold the teeth. Poor Steve just stood and looked horrified.

"Do I pull them all, or just the incisors?" Leroy was struggling for normalcy.

"Get the incisors first, then we'll decide." Revulsion was almost getting the upper hand with Dirk. Ashley's lips and bearded chin felt nasty.

Leroy made a couple of quick moves over Ashley's face and a tooth clattered into the bowl. It was long and hollow. "When I finish the extractions, I'm going to plug the holes and sew them shut."

"Hurry up!" Dirk was struggling to keep the jaw down.

Two more teeth clattered into my bowl. The bottom ones weren't hollow.

Ashley's body began to convulse as Leroy went for the last tooth, and Dirk swore as the jaw clamped shut on the tip of his little finger, but Leroy got the tooth and we all jumped back.

All those centuries of garlic and crosses and stakes at crossroads gave way to modern science as Ashley deteriorated before our eyes. It was not a pretty sight. None of the men noticed when I slipped the teeth into my pocket.

Leroy used the facilities of the forensic lab to dispose of what little remained of the body and incinerated the clothing. The next day was Saturday, but we took a chance and returned the isolation chambers. I couldn't blame poor Leroy for not wanting them around his lab.

We also typed a farewell note from Ashley, believing rightly that everyone would be so glad that he was gone that they wouldn't look for him. Rhinefeldt whined around a bit, but without Ashley people ignored him completely.

With Ashley's ultimate sensory deprivation, the deaths ceased and those persons already ill made gradual recoveries. The epidemic over, the Atlanta team pulled out without Leroy, and things got back to normal.

Before Christmas, I went to the toy store and bought one of those kits for making clear plastic gadgets that display whatever is put in them and made each of us a muffin shaped paper weight containing a tiny wreath surrounding an Ashley tooth. I don't know what Dirk and Steve did with theirs, but Leroy and I keep our set in the greenhouse, under the perpetual halogen light.

...Felicia Florine Campbell is Professor of English at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. She is also Executive Director of the Far West Popular and American Culture Associations and edits The Popular Culture Review. In addition to sharing her splendid short stories and commentary with us, Dr. Campbell is also working on an authoritative edition of popular culture scholarship in an undisclosed location.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

DANSE MACABRE is edited, produced, and published online by Adam Henry Carriere - Copyright (c.) 2007. All rights reserved. Attributed works copyrighted by individual authors or in the public domain. Contributors retain all publication and serial rights. Viewpoints expressed by contributors, in quotations used, or suggested by displayed graphics may not necessarily reflect the opinions of this online journal. Images appearing in this journal are either in the public domain or the copyright of individuals who produced the image in question. It is believed that the non-profit use of scaled-down, low-resolution images taken from references throughout the world wide web which provide critical visual analysis to writings posted on this site qualifies as fair use under United States copyright law. Any other uses of these images may be copyright infringement. Thus Spake Advocaten...

Moonlight Serenade

Menu de la lune

-

▼

2007

(11)

-

▼

October

(11)

- LATE BLOOMERS a Poem by Steven Kilpatrick

- Bush Worried About New ThreatPresident Bush is wor...

- A LOVE LETTER AT A TIME OF LOSS a Poem by Elizabet...

- THE DIRECTIONLESS, WITHOUT a Poem by Ed Casey

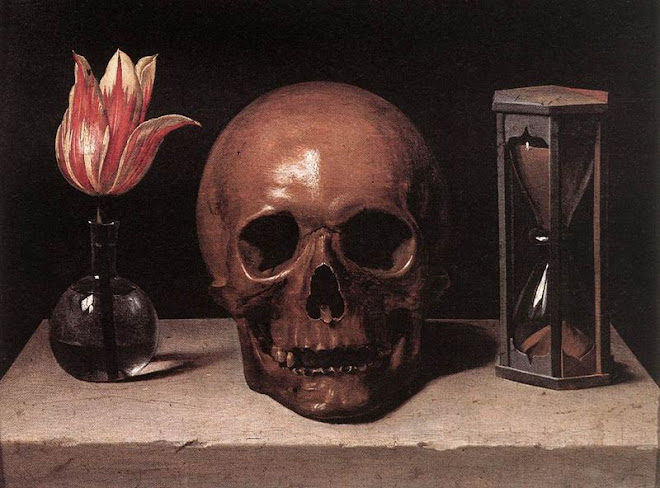

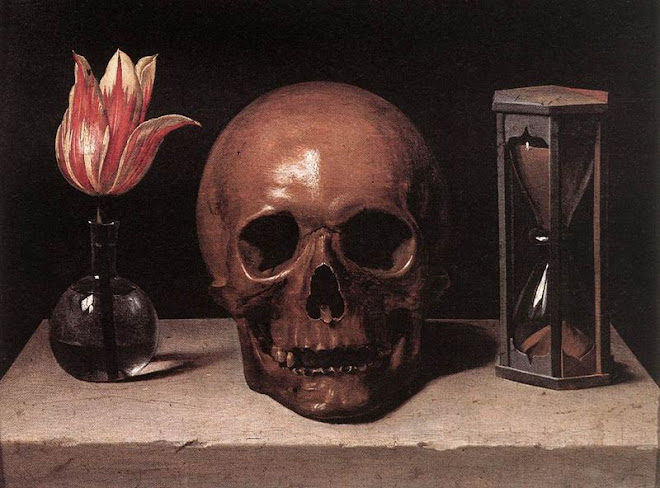

- portrait du macabre quatre

- DRAKULA an Ode by Robert David Michael Cerello

- TED'S DEAD a Short Story by Taylor Collier

- portrait du macabre six

- MAGNIFICAT a Poem by Elizabeth I. Riseden

- OCTOBER a Sonnet by Robert David Michael Cerello

- ASHLEY, IT'S SCARLET a Short Story by Felicia Flor...

-

▼

October

(11)

Archive du Danse Macabre

Toten-Tanz - ein Deutschespoesie

Sie brauchen kein Tanz-Orchester;

sie hören in sich ein Geheule

als wären sie Eulennester.

Ihr Ängsten näßt wie eine Beule,

und der Vorgeruch ihrer Fäule

ist noch ihr bester Geruch.

Sie fassen den Tänzer fester,

den rippenbetreßten Tänzer,

den Galan, den ächten Ergänzer

zu einem ganzen Paar.

Und er lockert der Ordensschwester

über dem Haar das Tuch;

sie tanzen ja unter Gleichen.

Und er zieht der wachslichtbleichen

leise die Lesezeichen

aus ihrem Stunden-Buch.

Bald wird ihnen allen zu heiß,

sie sind zu reich gekleidet;

beißender Schweiß verleidet

ihnen Stirne und Steiß

und Schauben und Hauben und Steine;

sie wünschen, sie wären nackt

wie ein Kind, ein Verrückter und Eine:

die tanzen noch immer im Takt

Rainer Maria Rilke

sie hören in sich ein Geheule

als wären sie Eulennester.

Ihr Ängsten näßt wie eine Beule,

und der Vorgeruch ihrer Fäule

ist noch ihr bester Geruch.

Sie fassen den Tänzer fester,

den rippenbetreßten Tänzer,

den Galan, den ächten Ergänzer

zu einem ganzen Paar.

Und er lockert der Ordensschwester

über dem Haar das Tuch;

sie tanzen ja unter Gleichen.

Und er zieht der wachslichtbleichen

leise die Lesezeichen

aus ihrem Stunden-Buch.

Bald wird ihnen allen zu heiß,

sie sind zu reich gekleidet;

beißender Schweiß verleidet

ihnen Stirne und Steiß

und Schauben und Hauben und Steine;

sie wünschen, sie wären nackt

wie ein Kind, ein Verrückter und Eine:

die tanzen noch immer im Takt

Rainer Maria Rilke

Todtentanz

danse le morte

Lo! I am Death! With aim as sure as steady,

All beings that are and shall be I draw near me.

I call thee,-I require thee, man, be ready!

Why build upon this fragile life?–Now hear me!

Where is the power that does not own me, fear me?

Who can escape me, when I bend my bow?

I pull the string,-thou liest in dust below,

Smitten by the barb my ministering angels bear me.

Come to the dance of Death! Come hither, even

The last, the lowliest,-of all rank and station!

Who will not come shall be by scourges driven:

I hold no parley with disinclination.

List to yon friar who preaches of salvation,

And hie ye to your penitential post!

For who delays,-who lingers,-he is lost,

And handed o’er to hopeless reprobation.

I to my dance–my mortal dance-have brought

Two nymphs, all bright in beauty and in bloom.

They listened, fear-struck, to my songs, methought;

And, truly, songs like mine are tinged with gloom.

But neither roseate hues nor flowers’ perfume

Will now avail them, -nor the thousands charms

Of worldly vanity;-they fill my arms,-

They are my brides,-their bridal bed the tomb.

And since ‘tis certain, then, that we must die,-

No hope, no chance, no prospect of redress,-

Be it our constant aim unswervingly

To tread God’s narrow path of holiness:

For he is first, last midst. O, let us press

Onwards! And when Death’s monitory glance

Shall summon us to join his mortal dance,

Even then shall hope and joy our footsteps bless.

Anonymous

All beings that are and shall be I draw near me.

I call thee,-I require thee, man, be ready!

Why build upon this fragile life?–Now hear me!

Where is the power that does not own me, fear me?

Who can escape me, when I bend my bow?

I pull the string,-thou liest in dust below,

Smitten by the barb my ministering angels bear me.

Come to the dance of Death! Come hither, even

The last, the lowliest,-of all rank and station!

Who will not come shall be by scourges driven:

I hold no parley with disinclination.

List to yon friar who preaches of salvation,

And hie ye to your penitential post!

For who delays,-who lingers,-he is lost,

And handed o’er to hopeless reprobation.

I to my dance–my mortal dance-have brought

Two nymphs, all bright in beauty and in bloom.

They listened, fear-struck, to my songs, methought;

And, truly, songs like mine are tinged with gloom.

But neither roseate hues nor flowers’ perfume

Will now avail them, -nor the thousands charms

Of worldly vanity;-they fill my arms,-

They are my brides,-their bridal bed the tomb.

And since ‘tis certain, then, that we must die,-

No hope, no chance, no prospect of redress,-

Be it our constant aim unswervingly

To tread God’s narrow path of holiness:

For he is first, last midst. O, let us press

Onwards! And when Death’s monitory glance

Shall summon us to join his mortal dance,

Even then shall hope and joy our footsteps bless.

Anonymous

Danse Macabre...

Oct / Nov 2007 Volume Two, Number Seven by Adam Henry Carriere. Copyright (c.) 2007. All Rights Reserved.

DANSE MACABRE is edited, produced, and published online by Adam Henry Carriere - Copyright (c.) 2007. All rights reserved. Attributed works copyrighted by individual authors or in the public domain. Contributors retain all publication and serial rights. Viewpoints expressed by contributors, in quotations used, or suggested by displayed graphics may not necessarily reflect the opinions of this online journal. Images appearing in this journal are either in the public domain or the copyright of individuals who produced the image in question. It is believed that the non-profit use of scaled-down, low-resolution images taken from references throughout the world wide web which provide critical visual analysis to writings posted on this site qualifies as fair use under United States copyright law. Any other uses of these images may be copyright infringement. Thus Spake Advocaten...